This month, we present a tribute to "Neo-Realism" – the cinematic movement that emerged in Italy at the end of World War II, confronting the horrors of the war and its aftermath. Thematically, Neo-Realist cinema arose as a reaction to the "white telephone films" – bourgeois comedies and dramas produced during the height of the Fascist regime, set in the stylized, sheltered world of the upper class. "Ossessione" (1943) – an adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice, widely considered the first Neo-Realist film – shocked Fascist censors with its raw portrayal of working-class life, desire, and passion.

In this context, the fight against the Nazis and Fascists, the end of the war, the devastated cities, and the harsh conditions of poverty and hunger became the material realities from which Neo-Realism emerged—as a humanist movement that placed the ordinary person at its center and sought to observe and understand them.

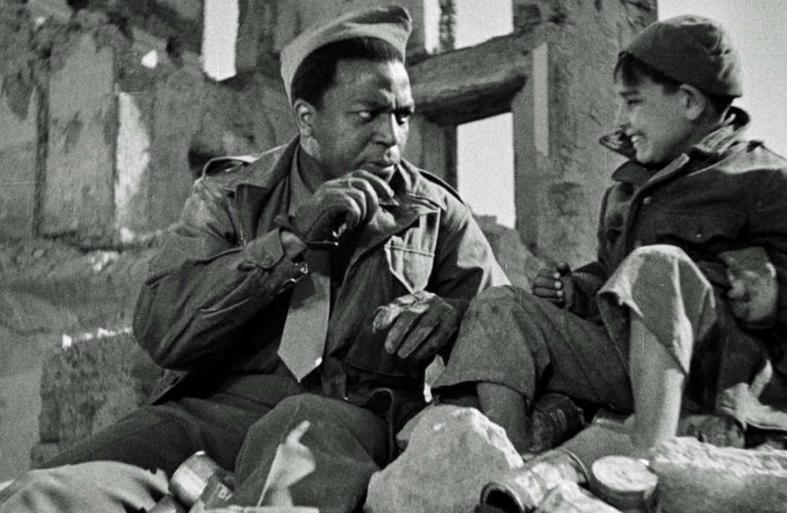

Stylistically, Neo-Realism was almost completely unmediated. Budgets were minimal, the Cinecittà studios lay in ruins; filming was done in the bombed-out streets of Italian cities, often using non-professional actors. The camera was frequently handheld, shaky, and reminiscent of documentary filmmaking. Yet essential cinematic tools were not abandoned: expressive camera movement, evocative sound design, and narrative structures that moved from crisis to resolution remained central.

In the years following the war, some of the most powerful and beautiful films of this movement—and of cinema at large—were created. "Rome, Open City", "Bicycle Thieves", and "La Terra Trema" captured the essence of a time and place, the struggle for survival, and its emotional cost. These films portrayed communities fighting for dignity and freedom during a time when institutions—the police, the church, the bank—were hollowed out and either unable or unwilling to offer support. Set against a backdrop of material and moral collapse, these stories unfold in a world without order, where individuals must decide for themselves—and for their communities—what is right.

With Italy’s postwar economic boom in the early 1950s, Neo-Realism gradually faded. Audiences began to favor more optimistic American films, and the new government was eager to avoid airing its "dirty laundry" in public. Yet the new chapter of Italian cinema that followed was no less compelling, carried forward by artists who emerged during the Neo-Realist period—Luchino Visconti, Federico Fellini, and others.